That 2018 Black Jeep Wrangler still shows up in my nightmares. The owner, a very successful and demanding guy named Dr. Miller, had given me the opportunity of a lifetime: a full high-end SQL (Sound Quality Loud) build. We were talking about a digital signal processor (DSP), three-way active front stage with silk domes, and a monster 12-inch sub in a custom-built, birch enclosure.

I spent four days on that Jeep. I deadened the doors, ran oversized OFC copper wires, and spent hours soldering every connection. It was perfect. On delivery day, I wanted to show off. I put on a heavy bass track, Dr. Miller climbed into the driver’s seat, and I—full of ego—turned the volume knob up to where I thought the system could handle it.

For thirty seconds, it was glorious. On the thirty-first second, the smell hit. A pungent, sweet, chemical odor filled the cabin. The highs, which were crystal clear moments ago, turned into a harsh, grating hiss. I saw a thin wisp of smoke curling out of the subwoofer port before I could dive for the volume knob. I had just fried $1,200 worth of gear in front of my best client. The culprit? Clipping.

What Exactly is Clipping?

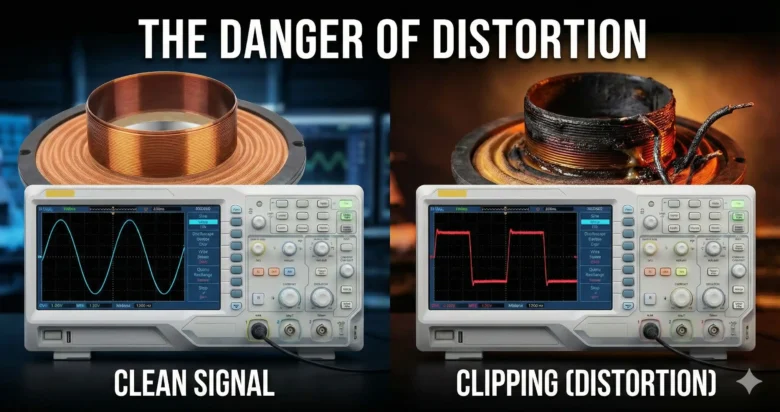

To explain to Dr. Miller what had happened, I had to stop being a “loudness” guy and start being a physics guy. Imagine your audio signal is a smooth, rolling ocean wave. It goes up and down with grace. This is what we call a Sine Wave.

Your amplifier has a physical limit, determined by its internal power supply voltage. When you demand more power than that voltage can provide, the wave “hits the ceiling.” Since it has nowhere else to go, the top and bottom of the wave are chopped off flat.

The wave is no longer smooth; it becomes a Square Wave. To your speaker, this looks like Direct Current (DC) for a fraction of a second. Speakers are designed for movement (AC), not for sitting still under high voltage (DC).

The Physics of Destruction: Why it Burns

Movement is what keeps a speaker alive. As the cone moves back and forth, it acts like a pump, pushing air across the voice coil to keep it cool.

When clipping occurs and the wave turns square, the cone literally “stops” for a millisecond at the very top and bottom of its stroke. During that tiny pause, the cooling stops, but the energy continues to pour into the coil. All that energy that should have been turned into sound is now turned into pure heat.

Furthermore, the actual power delivered during clipping is much higher than the rated RMS. Take a look at the power formula:

When a wave clips and squares off, the area under the curve (the total energy) increases significantly. A 500W amp can easily dump nearly 1000W of “dirty energy” into a speaker when it’s driven into heavy clipping. No voice coil can survive that for long.

Identifying Clipping Using Your Senses

After that “Jeep Incident,” I promised myself I would never trust my gut again. I trained my senses to act as a human oscilloscope.

1. The Ears: Your First Alert

In a subwoofer, clipping sounds “hollow” or “blunt.” The bass loses its sharp “kick” and starts to sound like a dull thud or a rattling “whoosh.” In door speakers, listen for the “S” sounds. If the singer’s voice starts to sound like a snake—hissing and harsh—that’s harmonic distortion caused by clipping. If the snare drums sound like someone crumpling paper, turn it down.

2. The Nose: The Point of No Return

If you smell it, the damage is already happening. The smell of a clipping coil is unmistakable: it smells like burning wood varnish mixed with hot ozone. It’s the protective enamel on the copper wire reaching 400°F. If you catch this scent, kill the power immediately. The coil is “cooking,” and even if it doesn’t fail today, its lifespan has been cut in half.

3. The Touch: The Dust Cap Test

This is a trick I use after every “heavy” demo. I reach over and feel the dust cap (the center) of the subwoofer.

- Cool or Lukewarm: Your system is perfectly tuned.

- Warm: You are pushing it, but it’s manageable.

- Hot to the touch: You are clipping. The heat from the coil is migrating through the former to the cap. Stop now.

4. The Eyes: The “Static” Jump

Watch the subwoofer cone. During clean play, the movement is a blur. During heavy clipping, the cone looks like it’s “jumping” or vibrating erratically without producing proportional sound. It may even look like it’s trying to stay at its furthest point of extension.

The Harmonic Trap: How the Sub Kills the Tweeter

This was the hardest part for me to understand back then. Why did Dr. Miller’s silk-dome tweeters fry when the clipping was coming from the subwoofer amp?

When a low-frequency signal clips, it creates what engineers call High-Order Harmonics. Essentially, the “dirt” from the bass signal creates high-frequency noise that bypasses the crossovers and goes straight to your tweeters.

The tweeter is a delicate instrument. When it receives a massive burst of high-frequency energy caused by the sub’s clipping, it gets overwhelmed and melts instantly. Golden Rule: Clipping in the basement (sub) eventually burns the roof (tweeters).

The “LED of Lies”

Many modern amps have a “Clip” or “Limit” LED. I used to rely on these, but the Jeep taught me otherwise. Some LEDs are only programmed to turn on when the amp hits 10% distortion. By the time that light is solid red, your speaker has been cooking for a long time.

Today, I use a digital multimeter to find the “Clean Voltage Ceiling” before the customer ever sees the car.

If my multimeter shows a value higher than this during testing, I know I’m in the danger zone, regardless of what the LED says.

The Client Handshake: Protecting the Warranty

Nowadays, when I deliver a car, I don’t just hand over the keys. I perform a “Client Education” ritual:

- The Volume Ceiling: I show them that while their head unit goes to 40, the “Safe Zone” ends at 32. I sometimes even put a small piece of tape or a mark on the dial.

- Gain vs. Volume: I explain that the gain knob is a “one-time setup,” not a “more bass” button.

- The “Stinky” Rule: I tell them, “If it smells like a chemistry lab, turn it off and call me.”

Conclusion: The Lesson from Dr. Miller

I had to replace Dr. Miller’s gear out of my own pocket to save my reputation. It was a bitter pill to swallow, but it was the best education I ever received.

Clipping isn’t just a technical term; it’s the physical wall of your system. Respecting that wall is what differentiates an amateur from a professional who can offer a lifetime warranty without fear. Learn to hear the “dirt,” feel the heat, and use the math.

Your client wants it loud, but they also want it to turn on tomorrow morning. Be the guardian of their voice coils.

FAQs

1. Is “soft clipping” safer than “hard clipping”? Some amplifiers have “soft clip” circuits that round off the edges of the square wave. While it sounds slightly better to the ear, it is still delivering excess heat to the coil. It is a safety net, not a license to crank the gain.

2. Why does my amplifier clip even if the gain is turned down? This is “Source Clipping.” If the signal coming out of your radio or DSP is already distorted (clipped), the amplifier will simply amplify that square wave. Your gain could be at zero, and you’d still burn the speaker.

3. Does a higher-powered amplifier prevent clipping? Yes, generally. A 1000W amp running at 500W is much safer than a 400W amp struggling to put out 500W. The larger amp has more “headroom,” meaning the signal stays clean and undistorted.

4. Can a crossover prevent clipping? A crossover cannot stop an amplifier from clipping, but it can protect a speaker from receiving the high-frequency harmonics created by clipping. However, it’s always better to stop the distortion at the source.

5. How do I explain “Gain” to a non-technical customer? Tell them it’s like the “Floor” of an elevator. You have to align the elevator floor (amp) perfectly with the building floor (radio) so people can walk across without tripping. If they aren’t aligned, the “trip” is the clipping that breaks the speakers.