I’ll never forget a Fourth of July weekend about a decade ago. A client of mine, Mike, had just finished a beautiful build in his Jeep Wrangler—four 12-inch subs and a massive 3,000-watt amp rack. He went out to the lake with his friends, cranked the tunes for three hours with the engine off, and had the time of his life.

Then came the moment of truth. When the sun went down and it was time to leave, he turned the key. Click. Click. Silence.

Mike had a top-of-the-line “High CCA” automotive battery, but he didn’t realize that his battery was a sprinter, not a marathon runner. He’d drained it so low that the plates had physically warped. Not only was he stranded, but that brand-new $200 battery was permanently damaged. He called me from the tow truck, and I told him the same thing I’m going to tell you: If you want to play while the engine is off, you need a different kind of chemistry.

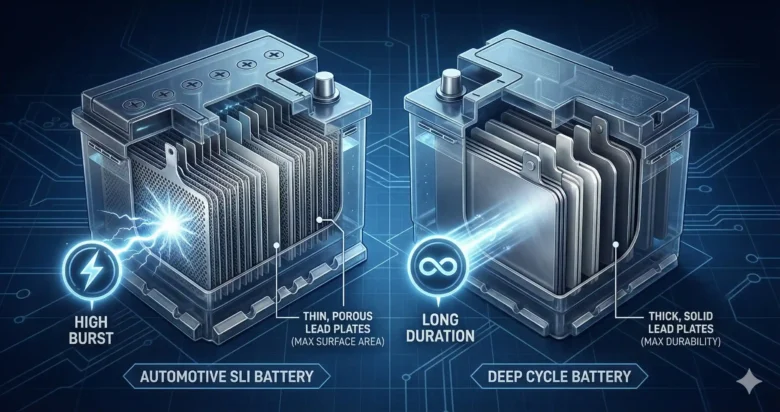

The Anatomy of a Battery: Why Plates Matter

To understand why Mike’s battery failed, we have to look inside the plastic case. All lead-acid batteries work on the same basic chemical principle, but their internal structure is optimized for different tasks.

The Automotive Battery (SLI): The Sprinter

SLI stands for Starting, Lighting, and Ignition. Its primary job is to deliver a massive burst of current (often 500 to 1,000 Amps) for about three to five seconds to turn over a cold engine.

- Plate Design: To deliver that much power at once, the battery needs a lot of surface area. Manufacturers use many thin plates with a sponge-like texture.

- The Flaw: These thin plates are fragile. If you discharge an SLI battery more than 20% or 30%, the chemical reaction begins to eat away at the thin lead, causing “sulfation” and structural failure.

The Deep Cycle Battery: The Marathon Runner

Deep cycle (often called stationary or marine) batteries are built for the long haul. They are designed to provide a steady amount of current over a long period.

- Plate Design: Instead of many thin plates, they use fewer, thick solid lead plates.

- The Strength: These thick plates can handle the chemical “stripping” that happens during a deep discharge without falling apart. You can drain a true deep-cycle battery down to 50% or even 80% thousands of times without killing it.

The Technical Specs: Ah vs. RC

When you go to buy a battery for your sound system, the labels can be confusing. For car audio, we care about two main numbers.

Amp-Hours (Ah)

This is the standard rating for deep-cycle batteries. It tells you how much total energy is stored in the battery.

Estimated Hours = (Battery Ah * 0.5) / Average Current Draw

Example: 100Ah battery, 20A average draw, 50% discharge limit.

(100 * 0.5) / 20 = 2.5 Hours of playtime.

Reserve Capacity (RC)

Automotive batteries often use RC instead. This is the number of minutes the battery can deliver 25 Amps before the voltage drops to 10.5V. While useful, it doesn’t give you the full picture of how the battery handles high-current music peaks.

Peukert’s Law: The Efficiency Killer

Here is a technical secret most installers miss: The faster you drain a battery, the less capacity it has. This is known as Peukert’s Law. If you have a 100Ah battery and you draw 5 Amps, it might last 20 hours. But if you draw 100 Amps, it won’t last 1 hour—it might only last 40 minutes.

t = H * (C / (I * H))^k

Where:

t = Time of discharge

C = Rated capacity (Ah)

I = Actual discharge current (Amps)

k = Peukert constant (usually 1.1 to 1.3 for lead-acid)

For a high-power audio system, this means that having one “massive” battery is often less efficient than having two smaller ones wired in parallel, because splitting the current draw between two batteries reduces the “Peukert effect” on each one.

AGM: The Best of Both Worlds?

In the last 15 years, Absorbent Glass Mat (AGM) batteries have become the gold standard for car audio. AGM is a technology where the electrolyte is held in glass fiber mats rather than sloshing around as a liquid.

- Vibration Resistance: Essential for cars with heavy bass.

- Low Internal Resistance: Allows the battery to charge and discharge much faster than a standard flooded battery.

- Hybrid Capability: Many high-end AGM batteries (like the ones from XS Power or Odyssey) are “Dual Purpose.” They have enough surface area to start an engine but thick enough plates to handle deep cycling.

If you are building a serious system, never use a standard flooded lead-acid battery. Always upgrade to AGM.

The Depth of Discharge (DoD) Trap

Every battery has a “Cycle Life” chart. It looks something like this:

- 100% Discharge: 50 cycles (Battery dies in 2 months).

- 50% Discharge: 500 cycles (Battery lasts 2 years).

- 10% Discharge: 2,000 cycles (Battery lasts 10 years).

If you keep playing your sound until the car barely starts, you are doing a 90% discharge. You are literally killing your investment. I always install a Voltage Meter on the dash. When the battery hits 12.1V, it’s time to start the engine. That is the 50% mark for most AGM batteries.

The Dual-Battery Strategy: The Pro Setup

The most reliable way to build a system is to separate the duties.

- Under the Hood: A standard AGM starting battery.

- In the Trunk: A massive Deep Cycle battery dedicated to the amplifiers.

- The Isolator: Use a high-current relay or a solid-state isolator between them.

When the engine is running, the alternator charges both. When the engine is off, the isolator disconnects the front battery. You can play your music until the back battery is dead, and the front battery will still have 100% of its power to start the car and get you home. This is how I fixed Mike’s Jeep, and he hasn’t needed a tow truck since.

Conclusion

If you only listen to music while driving, a high-quality AGM automotive battery is fine. But if you’re the guy who opens the doors at the BBQ or the car show, you must invest in deep-cycle technology.

Understand your Amp-hours, respect Peukert’s Law, and never let your voltage drop into the “danger zone” below 12V. Power is the foundation of sound. If your foundation is weak, your system will never reach its potential. Keep the plates thick, the voltage high, and the music playing.

FAQs

1. Can I charge a deep-cycle battery with a standard alternator? Yes, but it’s not ideal. Deep-cycle batteries often require a slightly higher charging voltage to reach a full 100% state of charge. If you use a large deep-cycle bank, I recommend a high-output alternator with an adjustable voltage regulator set to 14.4V – 14.7V.

2. Is Lithium (LiFePO4) better than Deep Cycle Lead-Acid? Absolutely. Lithium is the new frontier. It is 1/3 the weight, can be discharged to 95% without damage, and maintains a flat voltage curve. However, it is significantly more expensive and requires a specialized charging profile. For most “Old School” builds, a high-quality AGM Deep Cycle is still the most cost-effective ROI.

3. Why do deep-cycle batteries have a lower CCA rating? Because they have thicker plates, there is less surface area for the chemical reaction to happen “instantly.” This is why a 100Ah deep-cycle battery might only have 600 CCA, while a 100Ah starting battery might have 1,100 CCA.

4. Can I mix an old battery with a new battery in parallel? Never. The old battery will have higher internal resistance and will “drain” the new battery as it tries to equalize the voltage. Always replace batteries in pairs if they are wired together.

5. Does heat affect stationary batteries more than starting batteries? Yes. Deep-cycle batteries are sensitive to “Thermal Runaway.” Because they are often placed in trunks or enclosures without airflow, and they are charged for long periods, heat can build up and damage the internal separators. Always ensure your battery bank has some form of ventilation.