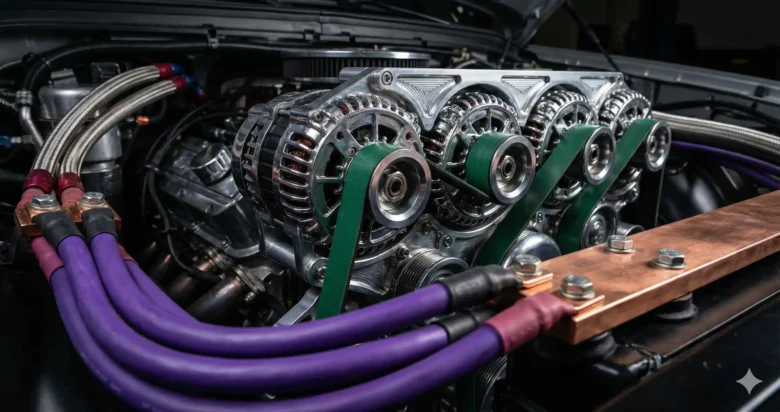

I’ll never forget the first time I saw the engine bay of a competition-grade Ford Excursion in Ohio. When the owner popped the hood, you didn’t see an engine; you saw a wall of chrome and copper. It was a custom bracket holding four High-Output Alternators, each rated at 300 Amps. The sound it made was a high-frequency electrical hum that signaled one thing: there was enough raw power here to light up an entire city block.

The owner explained that before this setup, he was “frying” expensive batteries every three months. No matter how many Lithium Batteries he added, his 40,000-watt RMS amplifier array was so hungry that his voltage would crash to 10V in seconds. With the quad-alternator setup, the needle stayed pinned at 14.8V, no matter how aggressive the bassline.

Installing multiple alternators isn’t just about “visual flex”; it’s an engineering necessity for those who have reached the physical limits of a 12V system. In this guide, I’m taking you inside the engine bay to show you how to design a power generation system that never bows down to the bass.

The Physics of Extreme Demand: Why 1,200 Amps?

In high-performance Car Audio, amperage is the fuel. If you have an amplifier system totaling 20,000 Watts RMS, the math is cruel and immediate. Considering the efficiency of a typical Class D amplifier, the current demand is astronomical.

Applying this to a 20,000W system at 80% efficiency on a 14.4V rail: 20,000 / 0.80 = 25,000 Input Watts. 25,000 / 14.4 = 1,736 Amps.

Even a massive Battery Bank cannot sustain this discharge for long without immediate recharging. This is where the High-Output Alternator array becomes the lifeblood of the build.

The Multi-Alternator Bracket: The Billet Foundation

You can’t just bolt four alternators to a stock engine and expect it to survive. The biggest engineering hurdle is the bracket. These are usually CNC-machined from solid blocks of 6061-T6 Billet Aluminum to handle the insane torque loads.

Critical Engineering Challenges:

- Belt Alignment: If the alternators are even 1mm out of alignment, you will shred a Serpentine Belt in minutes.

- Belt Wrap: You need maximum surface contact on the pulleys. This often requires extra idler pulleys to ensure the belt doesn’t slip under high load.

- Crankshaft Stress: The installer must ensure the extra mechanical drag doesn’t damage the crankshaft snout or main bearings.

Synchronizing the Giants: External Regulation

When you put alternators in parallel, they must “speak the same language.” If one alternator regulates at 14.2V and the other at 14.6V, they will fight. The higher voltage unit will take 100% of the load until it overheats, while the other sits idle.

The professional solution is an External Voltage Regulator. This unit bypasses the internal regulators and controls all four alternators as a single, massive unit. This allows you to dial in your voltage (e.g., 14.8V for LTO Lithium or 14.4V for AGM) and ensures every alternator shares the workload equally.

Thermal Management: Cooling 1,200 Amps

Generating 1,200 Amps creates an immense amount of waste heat. Each alternator becomes a high-powered heater under the hood. If the air doesn’t circulate, efficiency drops—a phenomenon known as “Heat Fade.”

Pro Cooling Strategies:

- Overdrive Pulleys: These make the alternators spin faster at idle, increasing internal fan speed.

- Air Ducting: In SPL competition, it’s common to see ducts bringing fresh air from the front grille directly to the rear of the alternators.

- Heat Sinks: High-end units often feature finned aluminum casings to increase surface area for Thermal Dissipation.

The Copper Infrastructure: 0 Gauge OFC and Busbars

Transporting 1,200 Amps requires an infrastructure that would intimidate most electricians. You don’t use a single wire; you use a “loom” of heavy-duty cables.

Each alternator typically has its own dedicated 0 Gauge OFC Cable run. These cables converge into a massive Copper Busbar before heading to the battery bank.

- Why Pure Copper? Aluminum (CCA) is forbidden here. The extra resistance of aluminum at 1,000+ amps would generate enough heat to melt the insulation and start a fire. OFC Cable is the only safe way to transport this much energy.

The Industrial-Scale Big 3 Upgrade

If you are pushing 1,200 Amps into the system via the positive post, that same current must return to the alternator through the chassis. A standard Big 3 Upgrade isn’t enough. You need to reinforce the engine block and chassis grounds with multiple 0-gauge cables to ensure the “return path” has zero bottlenecks. If the ground is weak, your expensive quad-alternator setup will underperform.

Safety and Circuit Protection: Controlling the Lightning

A short circuit in a 1,200-amp system is essentially an industrial arc-welder.

- ANL Fuses: Every single output cable from every alternator must be fused. If one alternator shorts internally, the others will dump 900+ amps into it, causing an explosion if not fused.

- Heat Shielding: Since these cables run near exhaust manifolds, using high-temp “tech-flex” and heat-shielding sleeves is mandatory to prevent the insulation from becoming brittle.

Conclusion: Engineering Without Compromise

Building a quad-alternator system is the ultimate expression of Car Audio engineering. It’s about more than just being loud; it’s about providing the electrical “pressure” required for high-fidelity, high-impact sound. By focusing on Billet Aluminum brackets, OFC Wiring, and external regulation, you turn your vehicle into a professional power station.

When your voltage stays at a rock-solid 14.4V during the most violent bass drops, you’ll know the engineering was worth it. Protect your gear, feed the beast, and let the music play.

FAQ

1. Does a quad-alternator setup affect gas mileage? Yes. Generating 1,200 Amps requires significant horsepower from the engine. When the system is at full tilt, it can sap 15-20 horsepower just to turn those alternators, which will noticeably impact fuel economy.

2. Can I use different brands of alternators in the same bracket? It is highly discouraged. For parallel synchronization to work perfectly, the alternators should have identical internal windings and turn ratios. Mixing brands often leads to uneven load sharing and premature failure.

3. Do I need a second belt? Most quad-brackets utilize a single, very long “heavy-duty” belt. However, some extreme builds use a dual-belt system to prevent slippage. If you hear a “squeal” when the bass hits, your belt is slipping and you are losing power.